PART 1, Episode 2 - Brusilow as assistant concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra.

Szell promised me a solo every year—a very generous deal for an assistant concertmaster. In most orchestras only the principal players soloed, but Szell liked to demonstrate publicly that the Cleveland Orchestra had quality below the surface.

The first year, he suggested the Sibelius Violin Concerto. I supposed either he or Joe had heard the broadcast of my performance of it with the Philadelphia Orchestra a few months earlier. (Szell was generous about approving my absences from Cleveland for soloing.) The first rehearsal loomed darkly over me because, where most conductors give a soloist free rein, Szell usually jettisoned that bit of etiquette and delivered minute instructions to the soloist.

Maybe he was in a good mood. He didn’t correct me at rehearsals or the performance, and he asked me to play it again the next week at Oberlin College.

In February the orchestra undertook its annual tour through various towns in Ohio and New York, stopping at Ithaca, at Troy’s little hall with the best sound anywhere, and then in New York City.

Wherever we performed, Joe Gingold and I were right at the foot of the conducting podium, Joe on the audience side and I on his left. We had a common experience. Those who sat farther back might not know that when Szell spat a word like stupid at the players, actual saliva came with the hiss.

The leadership required of a concertmaster was familiar to me. He is responsible for keeping the orchestra in tune and, equally important, his playing must inspire theirs. His intensity should be contagious. Other musicians will tend to follow his mood. Joe’s task in Cleveland took the job to a new level. He had to support the morale of men who are shouted at, insulted, and threatened.

Some days, the effort of straining to catch every nuance of criticism that Szell spat our way built into a collective pressure that had to find release. A good concertmaster accepts it as his responsibility to maintain the morale of the players.

Joe Gingold was an exceptional concertmaster. He signaled that he had a question, and Szell would stop and turn to him. Which meant everyone stopped and watched. Rapid sounds would come from Joe’s mouth, including lots of consonants. You would recognize a technical term in the middle—up bow or pizzicato. A sentence might end with a common phrase like do it. Joe’s face conveyed energized sincerity.

“What?” Szell would ask.

A hint of impatience would tug at Joe’s eyebrows. With a sigh, he might say, “Dannim phalima deepo we’ll do alum,” at breakneck speed, all of us trembling with the effort to suppress laughter.

“Well, I think you can use your own judgment there,” Szell might answer. Then he would resume conducting with his confidence slightly shaken. And we would play with lightened hearts.

The goof-off part of the musical life always did give me pleasure but the biggest benefit of my years of partnering with Joe was still the music. I have never worked off another musician so well, and I think for Joe it was a rare experience, too.

Every musician is an individual artist, and while the conductor is able to corral them into a collective sound, each is still, in some sense, playing his own music. The concertmaster leads the whole orchestra in many ways and the string section more particularly. For the first and second violins, Joseph Gingold was expected to choose ways of playing notes (on which string), bowings (where to start, when to reverse), and sometimes even personal interpretations. Usually the assistant concertmaster’s main responsibility, besides playing well, is knowing all these details sufficiently to fill in if the concertmaster gets sick.

It wasn’t like that with Joe. He liked to work as a team, and we figured out together what fingering to use and how to bow each passage. He always wanted to hear my interpretation of a piece and sometimes chose it over his own. The upshot was something extremely unusual in a first violin stand—we actually sounded like one violin. It was an exhilarating experience to connect with another artist in that way. For me, that deep aesthetic communication has always been one of the greatest joys of the musical life.

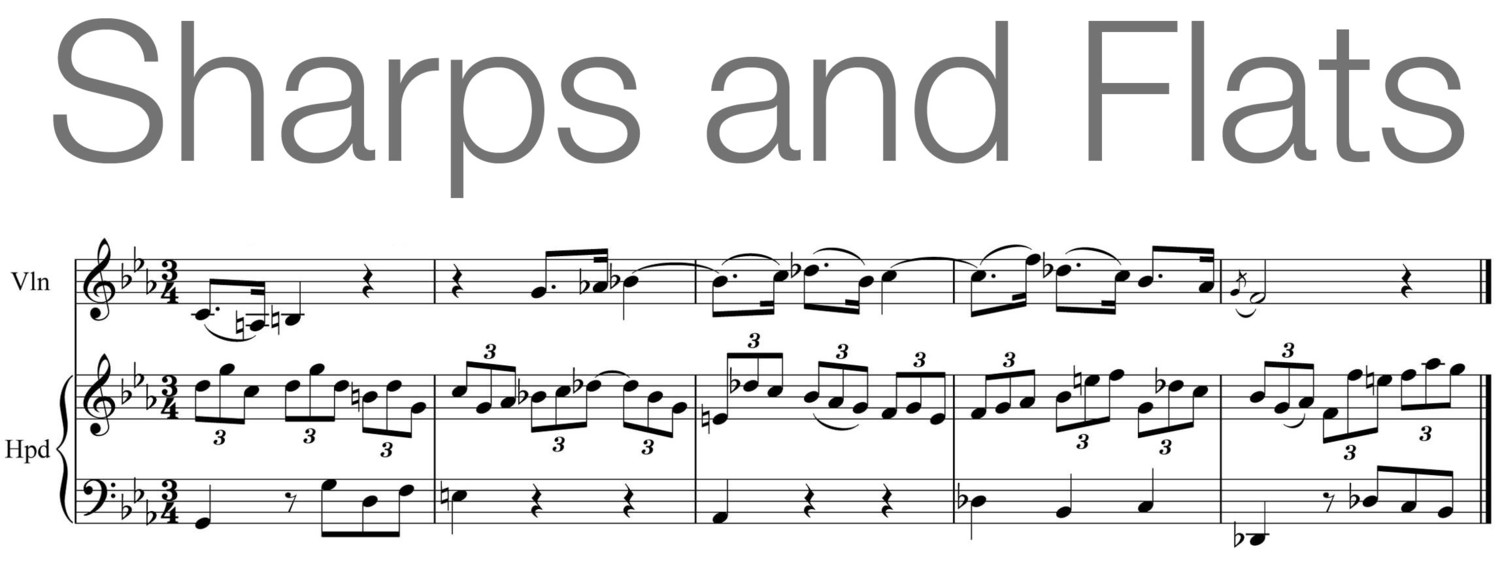

(Working on the violin solo in Strauss, “Till Eulenspiegel.”)

…I was satisfied with how it went in rehearsal. At the end, Szell appeared behind me. He did not offer comments but instead asked me to see him in his office. A happy thought sprang to mind—was he going to ask me to replace Rudolph Ringwald as his assistant conductor?

In his studio, he motioned me to sit at his own desk. Then he got something out of a music cupboard and came back. He slammed the score of “Till Eulenspiegel” down in front of me. “I don’t know where you think you got that god-awful interpretation today, but this is how Strauss wanted it to go!”

I was sitting at Szell’s desk. Had he motioned me there so that I would feel trapped? It worked. And I bethought myself—this man learned about “Till Eulenspiegel” from Strauss himself. I will take in every word. I opened the score to the beginning.

Szell sat at the piano and proceeded to play through the piece from memory, commenting as he played. “And this part speeds up right here—you were way too slow! It’s the clarinet sounding like Till’s laughter because he’s goofing off and thinks all is dandy. He has no idea he’s going to be hanged. That’s the melodic line here. You can’t just let every other instrument play loud during solos. You’ve got to emphasize his impish charm, his lollygagging in the busy marketplace.

“The change of atmosphere when the people get upset because he’s overturned baskets and carts—you totally missed that. The percussionist playing the ratchet didn’t get enough guidance from you. His part is central. That’s how we know Till really irritates everyone.

“You did okay with the clergy coming in, the pretentious viola passage. But you messed up with the violin solo. That’s Till at his most blasphemous. And he’s climbing the steeple. The tempo has to be like this to get him all the way up. The whole town sees him and points up there. The tempo changes—which you missed—and why do you think Strauss changes the tempo? Then the long glissando. Don’t you hear it? That’s when Till turns around and pees!

“Now the French horn has the melody. It’s the voice of Till again, still sassy but this time he’s nervous. Phrase it like this. Maybe he’s in trouble, but maybe he’ll get out of it. But you let the cellos take over. It was all wrong.

“And the bassoons in this part. They’re the academics, obviously! We have to hear them over the strings.

“Then you rushed the death scene! Slow the tubas down. Give the audience time to take it in, to mourn as Till dies. Especially that rest—they have to feel the silence. That gets the audience ready for the happy surprise when Till’s spirit comes back. Catch the amusement in that trill at the end.”

Here was a huge helping of the rich Germanic music tradition he had imbibed, flavored with vinegar.

PART I, Episode 3 - Brusilow invited to be concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy

When our regular rehearsals began that fall, Joe sent me to see Szell. “He has something to tell you.”

Szell opened his office door with a big smile on his face. “Come in, come in, Anshel.” He motioned me to one of the several chairs facing his desk, and took his own seat behind it. “I have something special to tell you.”

That much I knew.

Finally he said, “You are now the associate concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra!”

I said, “That’s wonderful,” which was an acceptable response to Szell. I should have stopped there, but instead I said, “Does that mean more money?”

He slammed his palm on the wooden desktop. “Money! What’s money?” It came out of his mouth with a grimace, reminding me of the old term filthy lucre. “You’re ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER OF ONE OF THE WORLD’S GREAT ORCHESTRAS!”

People who come to concerts often assume that the experience of playing your instrument before so many people must be all-consuming. They forget we have pasts, some of them terrible, and also present-day lives besides music. Backstage, they think, the musician sweats it out, studying the music again. And some players do suffer terrible anxiety. But we poker buddies were all about the cards in our hands and the small winnings we amassed. We were always being tapped and summoned by the other musicians, the ones who paid attention to the dimming of the lights in the hall— “Let’s go!” At intermission, we would count the seconds till we could decently amble off the stage out of sight, and then dash back to the table. The dealer—no one ever forgot whose turn it was— somehow got there first and was shuffling and dealing. Applause is all very nice, even standing ovations, but there were times when some of us wished they would quit already so we could get back to the important thing in life.

Musicians long before our time had figured out this method of survival. Szell said that sometimes Richard Strauss seemed bored with whatever he was conducting in rehearsal, as if he were “just serving time earning his fee and waiting for the card game that came after the performance.”

The Cleveland Orchestra did its usual spring tour eastward. Playing at Carnegie Hall was always thrilling. But we had to get there, and boredom was our traveling companion.

On train trips, the shuffling of cards began before the train pulled out of the station. On this particular tour, we entertained ourselves pretty well through New York State, stopping for concerts at places like Utica and Troy. One day I had a nice foursome of bridge going when Szell passed us on the train and looked into the compartment. We were just starting the bidding.

“One no-trump,” a player said.

Szell gave in to a wistful smile. “I love bridge. Hardly ever have time for it now.”

“Dr. Szell” - One of my companions was already on his feet. “Please take my place.”

“Oh, yes, you must!” we all said. We collected the cards and began redealing almost before he had time to decide. So he sat down for a moment’s relaxation as one of the guys.

A little shock went through us, such that we weren’t about to make eye contact with one another. Still, we were glad to have him. He seemed to have a decent hand and bid fairly aggressively till it was up to four hearts. He was the player and his partner the dummy for that hand. He made mistakes, and my partner and I set him by three tricks. It had been a makeable hand, just badly played.

“I’ve got such a headache,” he said. “I think I’d better go rest.”

It was impossible not to admire his relentless drive to nail the music. For the German composers, Szell had a natural feel. The Russians he did well enough by enforcing the letter of the law, so to speak. But perfectionism only gets you so far. Playing French music under him was a little strange. You couldn’t see the satin and lace, the candlelight reflected in silver serving dishes. The colorists, the impressionists, the elegance of Ravel—these were not available to him.

Let me say again that my debt to Szell is immeasurable. And yet, every one of us in the Cleveland Orchestra got heartily sick of having every note scripted, especially in solos. That devours the soul of the artist. Perhaps it’s that more than anything that goaded so many of the musicians to refer to him by various four-letter expletives. His meanness, however unfortunate, was born of a desire for artistic perfection.

The musical downside of this astute conductor’s technique was that as we became perfect, we became overcautious. Newspapers labeled us “brilliant,” but we felt as if we were playing scales. After a performance, while the audience was clapping and Szell was taking his bows, Joe Gingold would look at me and whisper, “So what?”

Our outstanding oboist, Marc Lifschey, was a fun-loving person, and we all liked him. My salient memory of Marc, though, was during a recording session. Leon Fleisher was playing piano with us. There was a long oboe solo. Marc played it and then he took his oboe apart.

“I can’t stand this anymore,” he said without actually looking at Szell.

“This is a recording session, Marc. I think your problem can wait till the session is over.”

“I can’t play anymore. Not with your stick in my face for every note.” He was now cleaning the oboe.

“What are you doing?” Poor Szell. It just didn’t compute for him.

Marc closed his instrument case and stood up. “I quit.”

I know there’s more to the story, but that’s the part I observed. He did leave for a year to play for the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Then he returned to Cleveland for several years. I think Marc found a better home when he became principal oboe in the San Francisco Symphony.